SHM Submits Comments on 2024 Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule

September 11, 2023

SHM's Policy Efforts

SHM supports legislation that affects hospital medicine and general healthcare, advocating for hospitalists and the patients they serve.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Department of Health and Human Services

Attn: CMS-1784-P

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure,

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), representing the nation’s more than 46,000 hospitalists, is pleased to offer our comments on the proposed rule entitled Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2024 Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicare Advantage; Medicare and Medicaid Provider and Supplier Enrollment Policies; and Basic Health Program (CMS-1784-P).

Hospitalists are physicians whose professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. They provide care to millions of Medicare beneficiaries each year and served their communities heroically while caring for hospitalized patients throughout the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to managing clinical patient care, hospitalists also work to enhance the performance of their hospitals and health systems. The unique position of hospitalists in the healthcare system affords them a distinctive role in both individual physicianlevel and hospital-level performance measurement programs. It is from these perspectives that we offer our comments on this proposed rule.

Conversion Factor Comments

CMS proposes a 2024 Medicare conversion factor of $32.7476, which is a reduction of 3.36% from last year. The AMA estimates the impact of the 2024 PFS conversion factor and other statutory changes will lead to a -3.01% payment rate for hospitalists next year. This payment cut follows several years of payment cuts for hospitalists in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. These cuts, combined with inflationary pressures, threaten practice sustainability and stand to worsen the on-going staffing and coverage shortages experienced by many institutions across the country.

Further, some of this reduction is attributable to the proposed implementation to “active” status of the O/O Visit Complexity Code G2211. This code, reflecting Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient's single, serious condition or a complex condition (Add-on code, list separately in addition to office/outpatient evaluation and management visit, new or established) will have profound redistributive effects, essentially taking reimbursement from facility-based practitioners and giving it to outpatient clinicians. This redistribution has already occurred as a result of the re-valuation through the RUC process of the outpatient visit E/M codes in 2018-2019, followed by the later revisions of hospital visit E/M codes for Emergency Department and Observation/Inpatient services.

SHM opposes the implementation of G2211 and joins the AMA RUC in citing questions regarding the lack of clarity around the purpose, use, and reporting of the code. While it is true that the complexity of managing outpatients has increased, hospitalized patients and outpatients are not independent siloed groups. Costs and complexity for facility-based patients, particularly those of a non-elective nature, have increased in parallel. Staffing shortages continue and labor costs for temporary physicians, as well as nursing costs, skyrocketed during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE), and have not improved significantly.

Due to increasing patient needs and volumes, nearly 60 percent of hospital medicine groups anticipate growth will be required to adequately serve patients, according to respondents of the 2023 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Despite the acute need to increase staffing, nearly 80 percent of groups reported unfilled positions, and in those groups, approximately 10 percent of their budgeted FTE positions remain unfilled. Added financial pressures through continued cuts in the MPFS, coupled with redistribution to outpatient care, will further exacerbate this dynamic. Staffing shorƞalls do and will continue to impact the quality, safety and efficiency of patient care in the hospital.

We continue urging CMS to explore how to redress this critical issue, including working with Congress to create a more stable payment system. We are deeply concerned continued cuts in the MPFS, combined with the pressures of inflation, will create a crisis in the healthcare system, causing patient care to suffer as a result.

Potentially Misvalued Services Under the PFS – CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223

CMS indicated an interested party nominated the Hospital Inpatient and Observation Care visit codes (99221, 99222, and 99223) as misvalued and welcomes comments on this nomination. The Hospital Inpatient and Observation Care family of codes were all restructured and revalued in the CY 2023 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) final rule.

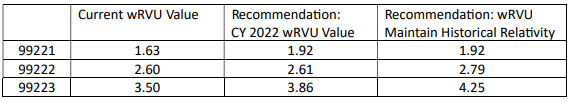

SHM continues to believe the Hospital Inpatient and Observation Care admission codes were not valued appropriately during the RUC process and their subsequent incorporation into the Medicare PFS as recommended by the RUC. As such, we strongly support the interested party’s nomination for 99221, 99222, and 99223 as misvalued. In our comments on the 2023 PFS proposed rule, we called out this misvaluation and asked CMS to either maintain the CY 2022 wRVU values for 99221-99223 or update the values to better align with the historical relativity between the office/outpatient and hospital-associated E/M codes, which is what the interested party has requested. We ask CMS to update the values of 99221-99223. Our two recommendations are listed in the table below:

We concur with the interested party’s assertions that the hospital setting typically sees more complex patients and higher severity conditions and comorbidities. CMS and other payers have been incentivizing and encouraging care to be delivered in the lowest, safest setting possible. An example of this is the increasing trend of performing joint replacements in outpatient ambulatory surgery centers as opposed to in hospitals. As a result of this financial and regulatory pressure, patients who receive care in the hospital are typically sicker, at risk of more complications, have more comorbidities, and otherwise require the higher level of care available in the hospital. This trend will only continue. While more services are being provided in outpatient settings, which in part explains increased values for office/outpatient E/M codes, patients in need of hospitalization require increased resources and expertise, justifying increased values for this E/M setting as well. We urge CMS to reconsider the values for 99221-99223 and to increase them to reflect the ever-growing complexity and difficulty of work in the hospital setting.

We also raise concern with the stepwise process by which the RUC reviewed and reassessed the value of all the E/M code families. By starting with the office/outpatient E/M codes, the RUC inherently disadvantaged every other E/M code family and disrupted the historical relativity between the families without engaging in a holistic conversation about the relativity of the entire E/M code set. The office/outpatient codes were compared against the historical value of hospital visit codes to update their wRVUs. The office/outpatient codes were subsequently increased, with most of the rationale being that costs, complexity, and technology have increased or changed. The factors used as a rationale for increasing codes in the outpatient space also affect other care settings, including the hospital. When the hospital visit E/M codes were reassessed, their values were compared against the new office/outpatient E/M values, and the discussion included concerned references to the financial disruptions caused by the prior revaluation of the office/outpatient E/M codes. In an October 2018 letter, SHM and two other specialty societies cautioned the AMA against engaging in a restructuring and revaluing of the E/M family in a piecemeal manner, warning that it would exclude and disadvantage sites of care reviewed subsequently. We believe this warning has become reality for the E/M code sets reviewed subsequent to the office/outpatient codes, most notably for 99221-99223.

Payment for Medicare Telehealth Services Under Section 1834(m) of the Act Requests to Add Services to the Medicare Telehealth Services List for CY 2024

CMS received a request to add hospital inpatient or observation care admission codes (99221, 99222, 99223), hospital inpatient or observation care admit/discharge same date (99234, 99235, 99236), and hospital inpatient or observation discharge (99238, 99239) to the Medicare Telehealth Services List on a permanent basis. These codes were added to the List on a Category 2 basis for the duration of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) and CMS proposes that they would remain available on the Medicare Telehealth Services List through CY 2024.

SHM supports the proposal to maintain these services as reimbursable by telehealth through CY 2024 and encourages CMS to include these services on a permanent basis. These codes were added to increase clinician and patient safety and prevent disease transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. While telehealth was effective at helping to reduce exposure to and the spread of COVID, it also had a very positive secondary impact of expanding the reach and capacity of hospitals and hospital medicine groups, particularly in their ability to provide care in rural and underserved areas. Post-pandemic, many healthcare systems, and the patients they serve, continue to rely on hospital-level E/M services via telehealth to address staffing shortages, geographical limitations, and other coverage challenges. Telehealth has been a critically important tool during the pandemic, and it continues to be an increasingly valuable and normalized tool that allows clinicians to deliver high quality medical care more broadly.

We continue to urge CMS to make permanent as billable by telehealth the hospital inpatient or observation care admission codes (99221, 99222, 99223), hospital inpatient or observation care admit/discharge same date codes (99234, 99235, 99236), and hospital inpatient or observation discharge codes (99238, 99239). While these services are not delivered via telehealth across all hospital settings, as already mentioned, the addition of these services has been important in rural and underserved hospitals. For example, rural hospitals, with fewer resources and often inadequate staffing levels, utilize telehealth admissions, particularly for night coverage, to stretch their limited resources and to ensure all beneficiaries receive the care they need and deserve. We believe the past several years of increased telehealth usage has provided CMS with valuable data about the usage and quality of care provided via telehealth. We also urge CMS to make public more data about utilization of telehealth codes to better inform stakeholders about the usage of telemedicine within the Medicare program.

Proposed Clarifications and Revisions to the Process for Considering Changes to the Medicare Telehealth Services List

CMS proposes to simplify the process for considering changes to the Medicare Telehealth Services List by replacing the Category 1-3 taxonomy with either a permanent or provisional designation. CMS would also redesignate any services currently on the list as a Category 1 or 2 would be “permanent” while any service added on a temporary Category 2 or Category 3 basis would be “provisional.” SHM is supportive of CMS’ proposed streamlining of the classification and the process for considering changes to the Medicare Telehealth Services List. We believe simplifying the designations for telehealth services will improve the transparency of what codes are available for reimbursement through telehealth. Frequency Limitations on Medicare Telehealth Subsequent Care Services in Inpatient and Nursing Facility Settings, and Critical Care Consultations CMS proposes to remove the existing telehealth frequency limitations for the Subsequent Inpatient Visit CPT codes (99231-99233), Subsequent Nursing Facility Visit CPT codes (99307-99310), and the Critical Care Consultation Services (G0508, G0509) for CY 2024 for the purposes of gathering more information about these codes’ use. These code sets currently have limitations of once every three days, once every fourteen days, and once per day, respectively. CMS waived the frequency limitations during the COVID19 PHE, and in reinstating the limitations at the conclusion of the PHE, noted they would consider changes to their policies in rulemaking. SHM strongly supports removal of the frequency limitations from these codes. Frequency determinations are much more appropriate based on medical necessity or the needs of individual patients, with guardrails established by the provision of further detailed guidance and the establishment of clear definitions of what is appropriate and reasonable.

Social Determinants of Health – Proposal to establish a stand-alone G-code

CMS proposes to create a new Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Risk Assessment code, GXXX5 (Administrations of a standardized, evidence-based Social Determinants of Health Risk Assessment, 5-15 minutes, not more often than every 6 months). CMS proposes the SDOH risk assessment must be furnished by the practitioner on the same date as they furnish the E/M visit. The SDOH needs must be documented in the medical record, have a duration of 5-15 minutes, and can be billed no more than every 6 months. This assessment could also be conducted via telehealth, as CMS is proposing to add this code to the Medicare Telehealth Services List. SHM has a longstanding commitment to addressing social disparities and believes it is critical to address social needs as part of delivering high-quality, effective care to patients with a wide range of social and economic needs that impact their care and health outcomes. We applaud CMS for putting resources behind what has been, to date, uncompensated and unrecognized work and for identifying social needs as a priority for the healthcare system through the creation of this G-code.

Hospitalization is an important, and sometimes only, touchpoint for patients accessing the healthcare system. Hospitalists and other members of the hospital medicine care team work to identify barriers or impediments to patient care and outcomes, both during hospitalization and after discharge. As such, we believe it is vital that hospitalists and other hospital-based healthcare providers be eligible to report GXXX5.

We note the frequency limitation may serve as a significant barrier for implementation of the G-code. The proposed frequency limitation of not more often than every 6 months may be appropriate in officebased care, such as a primary care provider’s office, where the clinician and the patient have a longitudinal relationship. Hospitalists and other hospital-based providers, on the other hand, have episodic relationships with patients. Given the fragmented state of EHR systems and challenges with interoperability, it would not be reasonable to assume that a risk assessment completed in the outpatient setting would be visible or accessible to hospitalists. They would, most likely, conduct risk assessments as part of their care and discharge planning processes. Therefore, hospitalists and their teams would conduct the risk assessments potentially without reimbursement due to the frequency limitation. Furthermore, as patient’s risk status can change drastically in very short periods of time, this can include something as simple as reliability of transportation or even driving limitations that were not present prior to a hospitalization. We urge CMS to reconsider this limitation to ensure this important element of care can be recognized during hospitalization.

SHM recently commented on a new measure, Addressing Social Needs, being developed by Yale-CORE for CMS. This measure, specified at the hospital level, would require both conducting risk assessments for social needs and arranging appropriate follow-up care. Through this measure, CMS is further centering social needs as a priority in the healthcare system. We wholeheartedly support this effort and encourage the agency to consider their payment policy creating GXXX5 and the alignment of mandatory measurement with that payment policy. For this reason, we strongly believe CMS should ensure this Gcode is accessible in all applicable care settings and avoid creating unfunded mandates through future quality measures.

CMS proposes to value GXXX5 with a work RVU of 0.18, proposing a direct crosswalk to the existing HCPCS code G0444 (Screening for depression in adults, 5-15 minutes). Given that this work has until now been uncompensated, we are not certain if this is an accurate valuation and estimation of the time associated with conducting the risk assessment. We encourage CMS to continue monitoring the code’s usage and solicit feedback in the future on whether it is sufficient for the work involved, particularly if CMS is considering adding services such as arranging follow-up to the code.

Evaluation and Management (E/M) Visits

Request for Comment about Evaluating E/M Services More Regularly and Comprehensively SHM would be supportive of more regular and comprehensive evaluation of E/M services. We continue to have concerns about the finalized valuations for some of the hospital inpatient and observation care services codes and, as previously stated, believe a more comprehensive approach to reviewing and revaluing the codes may have resulted in a more equitable outcome. We note the RUC process itself requires a certain level of expertise and familiarity with its methodology in order to effectively engage. However, this familiarity is difficult to develop when the codes used by hospitalists have only been reviewed once in the past twenty years. The healthcare system has changed – substantially – since the development of the RBRVS, and the emergence of hospitalists as a distinct specialty of clinicians is a perfect example. We look forward to future conversations with CMS about the future of the Medicare payment system.

Split (or Shared) Visits

In the CY2022 Physician Fee Schedule rule, CMS created a new time-based policy for billing a split (or shared) visit. Under this policy, a split (or shared) visit was defined as “E/M visit in the facility setting that is performed in part by both a physician and an NPP who are in the same group, in accordance with applicable laws and regulations.” Under the finalized policy, only the provider who performs a “substantive portion [of the visit]” would be able to bill for the entire visit. This policy defines a “substantive portion” as more than half the total distinct and qualifying time associated with the visit. However, CMS established a transitional period in which time, MDM, or History & Physical could be used to determine which provider performed the “substantive portion” of the visit. This transitional period was extended through CY 2023.

In the CY2024 proposed rule, CMS has proposed to further extend this transition period through at least December 31, 2024. CMS is proposing to maintain the current definition of substantive portion that allows for time, MDM, or history & physical. SHM is supportive of this continued delay and urges CMS to work with relevant stakeholders to develop a policy that better reflects the reality of team-based care. We appreciate CMS recognizes a time-based policy will be deeply disruptive to team-based care in the inpatient setting. We also continue to stress that a time-based policy will upend long-established billing and documentation systems, creating significant additional administrative burdens and costs in the inpatient setting. The daily patient care workflows of a hospitalist, which are often discontinuous, are not conducive to tracking time, and hospitalist groups from a wide variety of settings have reported difficulty implementing the tracking of time in a way that enables effective compliance with this new split (or shared) billing policy.

We note the AMA CPT Editorial Panel published their updated guidelines for split (or shared) visits on September 1, 2023. The new guidance covers when physicians and other qualified health professionals work together during a single E/M service for a patient and would allow for the performance of a substantive part of medical decision-making (MDM) for the service in addition to time to determine who can report the service. We are supportive of the new CPT guidance and encourage CMS to adopt this approach.

We strongly urge CMS either to adopt the new CPT guidance or otherwise develop a policy maintaining the use of MDM for determining which provider can bill for the split (or shared) visit. An attestation in the medical record will enable CMS to audit and ensure payments are appropriate without mandating time-based billing and jeopardizing the benefits team-based care bring to hospitalized patients. We do not believe the decision for which clinician should bill for a split or shared visit should involve devaluing the contributions of either clinician. To that end, we’ve continued to support the concept of a “meaningful contribution” to the care of a patient, as this reflects the value of having more than one clinician caring for the patient. If a physician makes a meaningful contribution to the care plan of a patient in a split or shared visit, that physician should be able to bill for the visit. A “meaningful contribution” could include directly managing the care of a patient, sharing decision-making with the APP, or other non-token involvement. We recognize CMS’ concern regarding the physician “poking their head in.” However, while a quick consult may take less time than a physical, for example, the consultation may completely alter the course of care, and the physician should be compensated for that contribution.

Our membership has voiced a variety of concerns about the time-based criterion, many of which argue “watching the clock” is a demoralizing and devaluing exercise for both the physician and the APP. In a team-based environment that does split or shared visits, the goal is to provide the best possible patient care. The time-based approach instead places significant focus on which clinician should get credit for the visit, distracting from what is most important – which is providing quality patient care.

Over the past two years, we received extensive feedback on the time-based policy from hospitalist groups in a range of employment and practice structures:

One prominent academic health system developed a highly successful physician/APP team-based model over the last fifteen years. This model has enabled the APPs to work at the top of their license under close physician supervision as allowed by their state. The synergy between the physicians and APPs on this team has led to enhanced patient care and patient experience. Furthermore, high-level physician supervision has helped identify 'near misses' of important diagnoses or treatment opportunities. This supervision has been particularly valuable when working with novice APPs. However, a solely time-based split (or shared) policy, if implemented, will make this very successful model untenable. It will no longer be financially feasible for physicians to oversee and closely supervise APPs. The physician’s supervisory work will very rarely exceed the time an APP spends on a patient, meaning the physician will not be compensated for their work. The time-only policy has resulted in some services to plan for their APPs to work independently without physician oversight, including new graduates with limited inpatient experience. Other services plan to eliminate the use of APPs and utilize only physicians for patient care. Both of these outcomes are negative, as it will move the institution away from its highly effective and efficient model of integrated, team-based care. Additionally, this policy created significant conflict between APP and MD leaders within the institution. The delayed implementation of the time-based policy has allowed the institution to retain its existing structures and best practices, although system leaders remain concerned about disruptions should the time-only policy be implemented.

Another large, national hospital medicine group did a pilot implementation of the proposed rule (i.e., based upon substantive time only, with no MDM path for split share) in a number of different hospital systems, care models, and local regulatory environments. For those sites that did split (or shared) visits and have more restrictive scope of practice bylaws, a competition of reported times emerged in the records. This group noted increased overlapping, rather than shared, work began occurring. For example, rounds would include both the physician and the APP, regardless of whether it was clinically necessary, for that time to be countable by the physician. As a result, APPs began to feel undervalued and unnecessary, seemingly relegated to function as highly trained scribes in those settings. At the same time, physicians who collaborate with and supervise APPs because they see it as good for the care of their patients began to feel as if they had to compete with their APP colleagues to be compensated for their work. If the physicians need to be present at every moment of the split or shared visit in order to count the time for billing purposes, there will be a push to phase out APP roles in some groups, as their work will become duplicative of the physician’s. The longer-term consequences of the time-based criterion for split or shared visits will be either elimination of APPs roles as skilled clinicians or a move away from team-based care to fully independent practice for APPs.

The team-based care models in hospital medicine developed out of necessity, as there are simply not enough physician hospitalists to care for all the hospitalized patients nationwide. Therefore, hospital medicine groups incorporated APPs into their teams and developed care models that enabled patients to receive high-quality care from a team of clinicians working to the fullest extent of their training. This time-based rule will increase job dissatisfaction, worsening the clinician shortage in hospital medicine (both physician and APP), negatively impacting patient access and patient care. CMS must develop a split (or shared) billing policy that fosters, rather than disrupts, team-based care in the hospital.

Medicare Provider Enrollment Provisions

CMS proposes to add certain misdemeanor convictions to the list of events that may precede revocation of a provider or supplier’s enrollment, including fraud or misconduct involving participation in a federal or state health care program, assault, battery, neglect, or abuse of a patient, or any other misdemeanor that places the Medicare program or its beneficiaries at immediate risk. We have concerns about recent state trends in criminalizing certain procedures and the potential unanticipated impact of this proposal when it comes to the provision of reproductive health care services following the 2022 Supreme Court decision handed down in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The radically altered and often uncertain legal landscape for reproductive health care following Dobbs has created a credible fear among clinicians that they could be prosecuted for providing, or even counseling on, various reproductive health care services. State-by-state criminalization of otherwise nationally-accepted standards of care do not merit revocation of Medicare enrollment.

Updates to the Quality Payment Program

Request for Feedback on Promoting Continuous Improvement in MIPS

CMS asks for feedback about what policy changes or approaches they might take to promote continuous improvement in care delivery and patient outcomes. SHM encourages CMS to keep the following points in mind as it thinks about the future of the MIPS.

Before moving towards increasing requirements or rigor within the program, we urge the agency to reconsider whether the MIPS as currently structured is meeting its goals in improving care quality. Our members commonly report the structure of the MIPS makes the program a compliance exercise, rather than a tool for quality improvement. Furthermore, for hospitalists and many other specialties, relevant quality measures are scarce and do not reflect the breadth or depth of care provided. Specifically, hospitalists have four measures in their MIPS specialty set. Two of the measures are broad based (Advance Care Plan Quality#047 and Documentation of Current Medications in the Medical Record Quality#130) and two are specific to heart failure (Quality#005 and 008). These measures do not represent the heterogeneity of hospitalized patients or the scope of hospitalists’ clinical expertise and responsibilities. In general, cost measures are not aligned with quality measures. As such, it is difficult to assess the “value” of care while looking at cost measures.

CMS should also consider how additional reporting requirements and programmatic difficulty will increase administrative burden. For hospitalists, the MIPS is just one of multiple programs intended to measure the quality of care for their patients, each requiring additional financial and staffing resources to participate. We do not believe it is appropriate at this time for CMS to consider adding complexity or difficulty to the MIPS program as post-PHE resources, both financial and adequate staffing, remain stretched beyond capacity. We urge CMS to explore policies to reduce the burden on physician groups. For example, CMS could work alongside EHR vendors to develop seamless measure workflows integrated into their products.

We also encourage the agency to increase its focus on long-term goalsetting for the healthcare system. The MIPS, as it currently functions, creates a set of ever-changing clinical targets. Measures consistently rotate in and out of the program, and there are no measures holistically evaluating hospitalists’ work. Unlike hospital-level programs, where measures represent evergreen targets for quality improvement, the MIPS does not have clearly established targets. To better align the MIPS with long-term goal setting, CMS could, for example, look to the most common diagnoses in certain settings or specialties/subspecialties to help identify appropriate clinical targets.

We do not believe that CMS should move towards eliminating measure selection in the program by adding required measures and other activities. Clinicians and groups should have the flexibility to select measures they feel best represent their work and patient population.

SHM is wary of the unintended consequences of establishing more rigorous policies, requirements, and performance standards. For individual clinicians, the constant barrage of requirements and measurement with no discernable benefit contributes more to burnout than true quality improvement. Further, if by virtue of being previously successful in the program, a group is asked to meet higher standards and subsequently achieves a lower performance score, CMS may inadvertently disincentivize continuous improvement efforts. It would also skew comparisons of the total performance scores between groups who are scored using more rigorous policies and those who are participating at the baseline MIPS policies.

Facility-based Score for Subgroups

CMS proposes to modify its policies to calculate a facility-based score for groups participating in an MVP, but not for groups electing to report as a subgroup. We believe MVP participants should have access to the same facility-based measurement scoring rules as traditional MIPS participants but oppose the proposed exclusion of subgroups. We urge CMS to develop a mechanism to enable subgroups to receive a facility-based measurement score. We note facility-based measurement can be applied at the group or individual level and do not believe there are barriers to calculating a facility-based measurement score in an MVP. As a longstanding proponent of a facility-based measurement option in the MIPS, SHM encourages CMS to pursue facility-based measurement as a more integrated feature of MVP reporting, particularly for subgroups.

Removal of Simple Pneumonia with Hospitalization Measure

CMS proposes to remove the Simple Pneumonia with Hospitalization Measure beginning with the CY 2024 performance period/2026 MIPS payment year. This measure has been suppressed from the program for several years due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As CMS indicated, the measure logic is unable to capture a significant portion of patients who have pneumonia due to COVID-19, rendering it a less complete measure of costs associated with this condition. SHM strongly supports removal of the measure and would welcome the opportunity to provide feedback and work with CMS on refining the measure specifications for future implementation.

Data Completeness Criteria

CMS proposes to maintain the data completeness threshold for quality measures at 75% through the CY 2026 MIPS performance year and increase the data completeness threshold to 80% beginning with CY 2027 MIPS performance year. We oppose the proposal to increase the data completeness threshold. We encourage CMS to examine challenges for clinician data aggregation, particularly when practice sites use different EHR systems. Some sites may struggle to aggregate data because EHR systems allow for customization, meaning the data may not be collected in a consistent manner across sites, even within the same EHR system. Different versions of EHR systems may also impede complete data collection. We believe the current threshold still provides an acceptable snapshot of a group or an individual’s performance on a measure, while maintaining flexibility for operational and implementation challenges participants may face.

MIPS Performance Threshold

CMS proposes to modify their methodology for establishing the performance threshold by creating a three-year “prior period” to identify the mean or median as required by the statute. CMS further proposes to use the mean of the prior period for the 2024, 2025, and 2026 performance years. For the 2024 reporting year, CMS intends to use 2017, 2018 and 2019 as the prior period, and set the 2024 performance threshold of the mean performance from those years at 82 out of 100. SHM generally supports CMS’ proposal to use the mean of three-years of performance to set subsequent years performance thresholds, however we do not believe the MIPS performance threshold should be increased for the 2024 reporting year. We oppose the proposal to set the MIPS performance threshold at 82 for the 2024 performance year and encourage CMS to either maintain or decrease the performance threshold from its current 75 points.

SHM does not believe it is appropriate for CMS to continue increasing the performance threshold in the wake of the significant and continued disruptions in the healthcare system in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are staffing shortages throughout the country, and healthcare resources are stretched to their limits. We therefore urge CMS to maintain the current performance threshold of 75 points. We also have concerns about using the performance thresholds from any of the prior years, as nearly every year had some unique programmatic circumstances or unavoidable pandemic-related challenges. This includes the Pick Your Pace approach to participation in 2017 and extreme and uncontrollable hardship exceptions requested for the 2019 reporting year due to the start of the pandemic when data was due for submission.

Request for Information: Publicly Reporting Cost Measures

CMS requests information about their future plans to publicly report cost measures. CMS has been publicly reporting data from quality measures, improvement activities, and Promoting Interoperability on the Compare profile pages, but has yet to report any cost scores or data. CMS is considering how they might publicly report cost information potentially including the category score or performance on specific measures, given that there are 25 measures already implemented or proposed for inclusion in the 2024 performance year.

While SHM generally supports public reporting and transparency efforts, we have several reservations about public reporting of the existing cost measures. Our general experience with the existing cost measures is they are difficult to understand, and performance results are difficult to interpret, even among hospitalists and hospital medicine administrators who consistently analyze this type of data. We believe it will be even more challenging for patients and the general public to understand, contextualize, and meaningfully interpret information from MIPS cost measures. We offer the following additional comments about public reporting of cost measures:

- Need for significant educational resources to decipher cost data. As mentioned above, hospitalists and group leaders find the measures and data they produce to be difficult to comprehend. We believe any sort of publicly reported cost measures will require significant educational resources paired with the public data.

- Lack of complementary quality measures. We believe the necessary context to make cost data speak to the value of care provided comes from complementary quality measures. Cost data alone does not illustrate patient outcomes, patient experience, or the safety and efficiency of a clinician. Even benchmarks or national averages of costs do not give patients information to help them decide about their clinicians and the relative quality of care they can expect. We believe CMS should not publicly report on cost measures until there are sufficient complementary quality measures to help give beneficiaries a snapshot of the overall value of care from their clinicians.

- Potential pressure for increased spending and utilization. Public reporting of cost measures, particularly without complementary outcome measures, may have the unintended consequence of incentivizing patients to seek care from higher cost clinicians. It is not uncommon for “more” and “more expensive” care to be perceived as “better,” and public reporting of cost measures may play into that mindset. This may also further aggravate healthcare disparities, by diverting resources from more under-resourced practices and potentially lead to higher out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries.

- Perception that CMS is trying to restrict care. We are concerned that public reporting of specific cost measures may lead patients to perceive CMS as trying to cut back on care available to them. While this is not the stated purpose, it is an easy assumption when performance on cost measures is reported in isolation from complementary quality and outcome measures.

- Public reporting of cost and utilization measures may be more meaningful for certain specialties or sites of service. Hospitalists are generally not “selected” by their patients. They see patients who are hospitalized and therefore, public reporting of quality measures in driving “choice” is of limited utility for patients.

- Other cost information, like the price transparency rules, may provide more actionable information to patients/consumers. CMS has other initiatives, like the price transparency rules, that may be more meaningful to beneficiaries. We recommend CMS focus its efforts on data that is most meaningful to patients, even if it is not from the MIPS.

Conclusion

SHM appreciates the opportunity to provide comments on the CY 2024 Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule and looks forward to continuing to work with the agency on these policies. If you have any questions or require more information, please contact Josh Boswell, Chief Legal Officer, at jboswell@hospitalmedicine.org.

Sincerely,

Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM

President, Society of Hospital Medicine